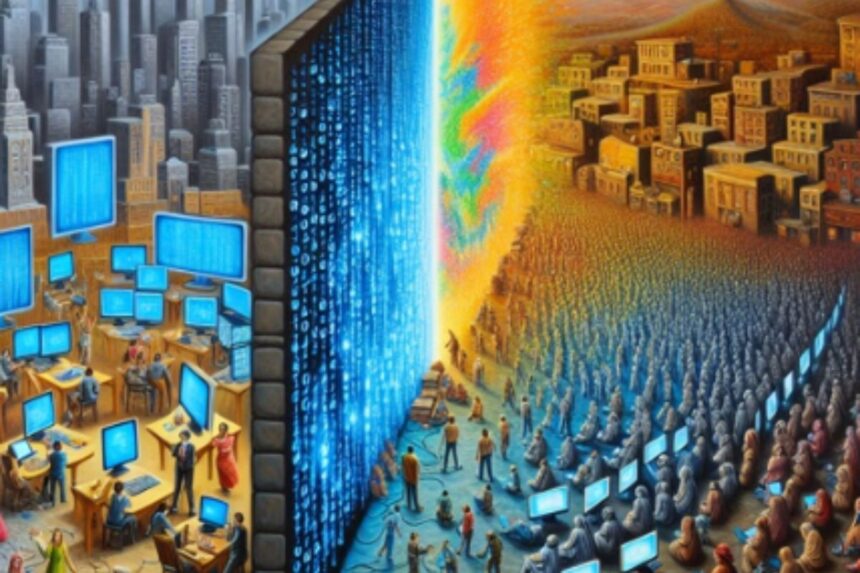

Numerous social media accounts of prominent voices in the Palestinian community, both in Gaza and in the diaspora abroad, are experiencing shadowbanning – which puts the user affected in a bubble where they are not readily made aware that their content is being hidden to the crowd – and banning of accounts altogether. This has also happened to verified accounts of Palestinian journalists documenting the unfolding horrors in real time, and rebalancing the perception of what is happening in the area. Instagram accounts were repeatedly suspended and then reopened for several days during which Meta claimed to be carrying out checks, which rarely ever highlighted violations of the guidelines – leading to hypothesize that this intermittent silencing is in itself the goal, whether or not the contents are complying with policy.

Situations like these are endemic on the social networks managed by Meta, X (formerly Twitter) and TikTok, over whose heads hung the official deadline that the European Union had assigned to evaluate the efforts of these private companies in “countering the spread of terrorist and violent content, incitement to hatred and misinformation.” The Palestinian militant group Hamas is listed as a terrorist group in the EU, and the European Commission underlined the legal requirement of social media companies to prevent spread of content that can be associated with Hamas.

With increasing numbers of palestinian social media accounts being disrupted, leading to claims of targeted censorship, it’s difficult to understand the definition of what content is considered “associated with Hamas”. This is especially true about a war that is frequently named the “Israel-Hamas war”, shadowing the very existence of non-militant Palestinian civilians that are experiencing repeated violence both in Gaza and in the West Bank.

Past social media companies’ influence

The silencing of Palestinian content that we are currently seeing is the last of a series of similar behaviors, as Human Rights Watch this year reports that Facebook was already silencing content on Palestine in 2021. Instagram, owned by Facebook, had been reported to remove posts and reposts about the escalation of violence in May 2021, including material on human rights abuses, once again with the motivation that these materials included “hate speech or symbols”.

This bias in content visibility only surfaced after the involvement of independent third-party entities, like BSR, that conducted investigations into the content moderation approaches used by social media giants. Digital rights organizations like 7amleh and political NGOs were pivotal in pressuring Facebook in 2021, and were ultimately successful in obtaining a review by Meta’s human rights division regarding “policies addressing incitement, the glorification of violence, and praise for terrorism.” In parallel, these NGOs attracted criticism for using the “apartheid” label to identify Israel’s policies, as well as for embracing the Boycott Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement approach to target Israeli industries and banks.

The far reach of media narratives

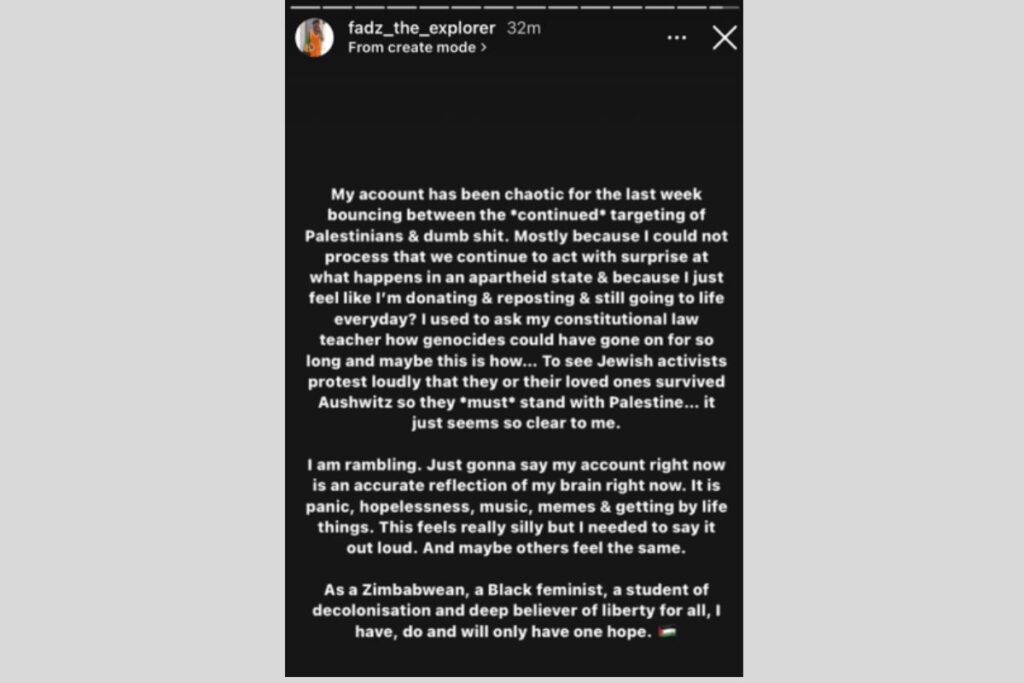

Media narratives reach into many other dimensions, although their impacts are sometimes intrinsically difficult to perceive in their entirety precisely because of the information imbalance. Since 1967, Palestinians have created the watermelon ploy to dissent from a ban imposed by Israel on displaying the Palestinian flag, a ban that has returned in 2021. Today we see many European countries criminalizing pro-Palestine demonstrations, also penalizing acts and symbols of solidarity, even with repercussions on people’s professional lives. One notable example comes from Ofcom, the UK’s communications regulator. Fadzai Madzingira, Ofcom’s Director of Online Safety Supervision, was suspended from her role “pending further investigations” after describing Israel as an apartheid state on her personal Instagram account, whilst describing herself as “a Zimbabwean, a Black Feminist, a student of decolonization”.

Another example is Michael Eisen, editor-in-chief of the open-source life sciences academic journal eLife, who shared on X (formerly Twitter) an article from satirical news site The Onion with the headline “Dying Gazans Criticized For Not Using Last Words To Condemn Hamas.” Einsen responded to the piece saying “The Onion speaks with more courage, insight and moral clarity than the leaders of every academic institution put together. I wish there were a TheOnion university.” Following this, eLife’s board of directors decided to replace Eisen as editor.

In both of these instances, people who chose to call out the colonial nature of the state of Israel as well as the bias in news reporting faced important consequences in their professional lives, with their respective organizations distancing themselves from those statements.

The media narrative shapes Islamophobia

The narrative shapes the Islamophobia that people in the Muslim community, and anyone who is Muslim-passing, know too well. It is undeniable that both antisemitism and islamophobia are at risk of increasing in Europe and globally, but as the definitions of each become more blurred in media depictions we should pay attention to its consequences.

When the Israeli ambassador says “This is our 9/11” to the United Nations, and US and Western officials echo him, our mind should inevitably remember the rhetoric of that terrible day which hid the previous events that led to that climax. The United States politics, just like Israel’s, have contributed to the overwhelming Islamophobia which dominated the narrative of these events and which is, to this day, rooted in the Western media way of thinking.

Information becomes part of the war.

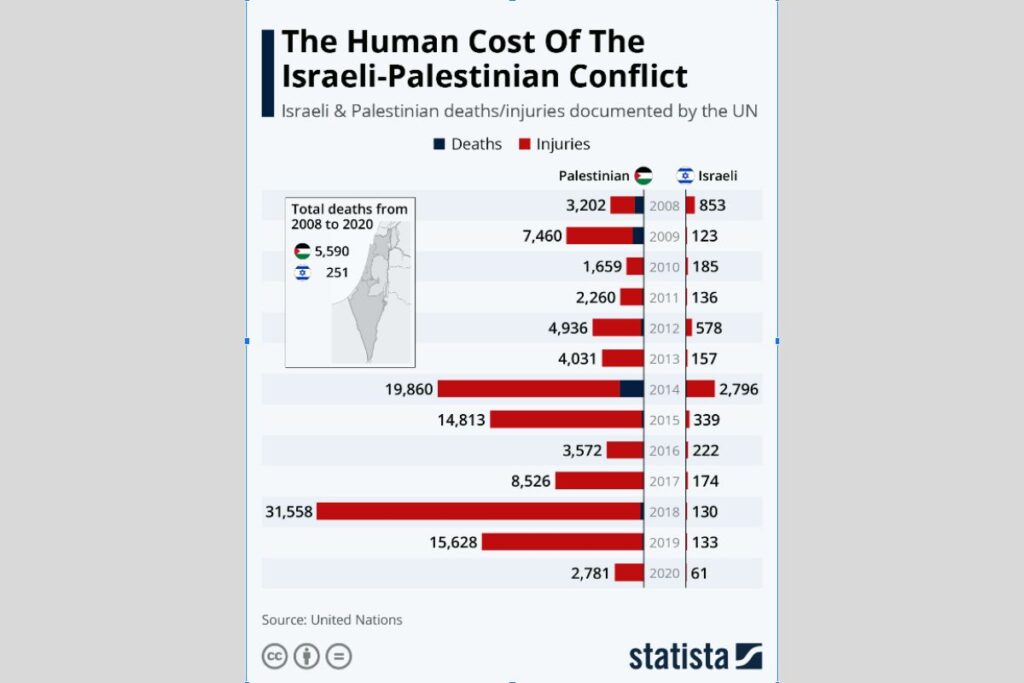

While the vision narrows on a forensic dissection of the missile that hit the Al-Ahli hospital, and while journalistic rigor wants us to avoid speculation, time seems to slow down and we lose sight of the balance of civilians killed that hangs irrefutably for the Palestinians, together with everything that preceded October 7, 2023. When time slows down to rightfully allow for independent investigations to take place, we tend to set aside the context and the historical trends surrounding these political actors. An example of this is US president Joe Biden stating on October 25th that he has “no confidence in the number that the Palestinians are using” for the death toll, despite UN and WHO officials confirming that such numbers provided from Gaza over the years are reliable. Biden has also propagated the claim of beheaded Israeli babies, solely based on Israeli media reports, showing inconsistency in treating information from both sides. In the past weeks, Israel’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs has started a PR campaign on Youtube and X stating that “Israel is under attack. We will make sure that those who harm us pay a heavy price.” mentioning the same unverified claim of Israeli infants murdered by Hamas.

At the center of the narrative framework we do not find the numerous war crimes reported by Amnesty International; we do not find the collapse of the health system on which the Palestinians rely during uninterrupted carpet bombings; we do not find the collective punishment illegal under international law that takes away basic necessities from Palestinians; nor we find the words of the United Nations which described the bombing of hospitals and schools as crimes against humanity and calls for the prevention of genocide.

The only losers in this media game are Palestinian civilians, and in the end they are the ones who suffer the damages of a narrative that hides colonialism, genocide, and Western exceptionalism.

What lies behind the media narrative

Knowing that 50 to 65% of the remaining oil reserves are in the Middle East, we can begin to understand Israel’s role for the West’s stronghold in the area. Meanwhile, Iran is calling on all other Arab nations to implement an oil and gas embargo on the nations that support Israel, but these are the same neighboring countries that have received criticism for abandoning the Palestinian cause due to increasing dependence on the West during the normalization process with Israel. There is ideology “on both sides” of the conflict that is used to cover extractive colonial politics.

There are several structural systems that favours Israel’s – and Western – narrative. These systems work by assuring a continuous lack of accountability, as Israel’s strongest western allies oversee the Security Council (with the US vetoing all meaningful attempts to bring Israel in front of the ICC) and by consolidating the media narration of events. These politics of colonisation, and Western exceptionalism and entitlement are at the core of not only the Palestinian genocide but also the one experienced by the people of Congo, whose lives are currently being lost in their millions.

Echoing what Fadzai Madzingira posted on her Instagram account, as “students of decolonisation” it is important to center colonialism and imperialism in our narrative frameworks, and promote independent media that has the freedom to lead these conversations.